Login

19 Nov

In the latest of his Diagnostic Dilemmas series, Francesco Cian reviews the case of a nine-year-old German Shepherd dog presented with a one-week history of anorexia, lethargy, stranguria and haematuria.

Francesco Cian

Job Title

A nine-year-old male, neutered German Shepherd dog presented to the referring veterinarian with a one-week history of anorexia, lethargy, stranguria (painful, frequent urination of small volumes) and haematuria.

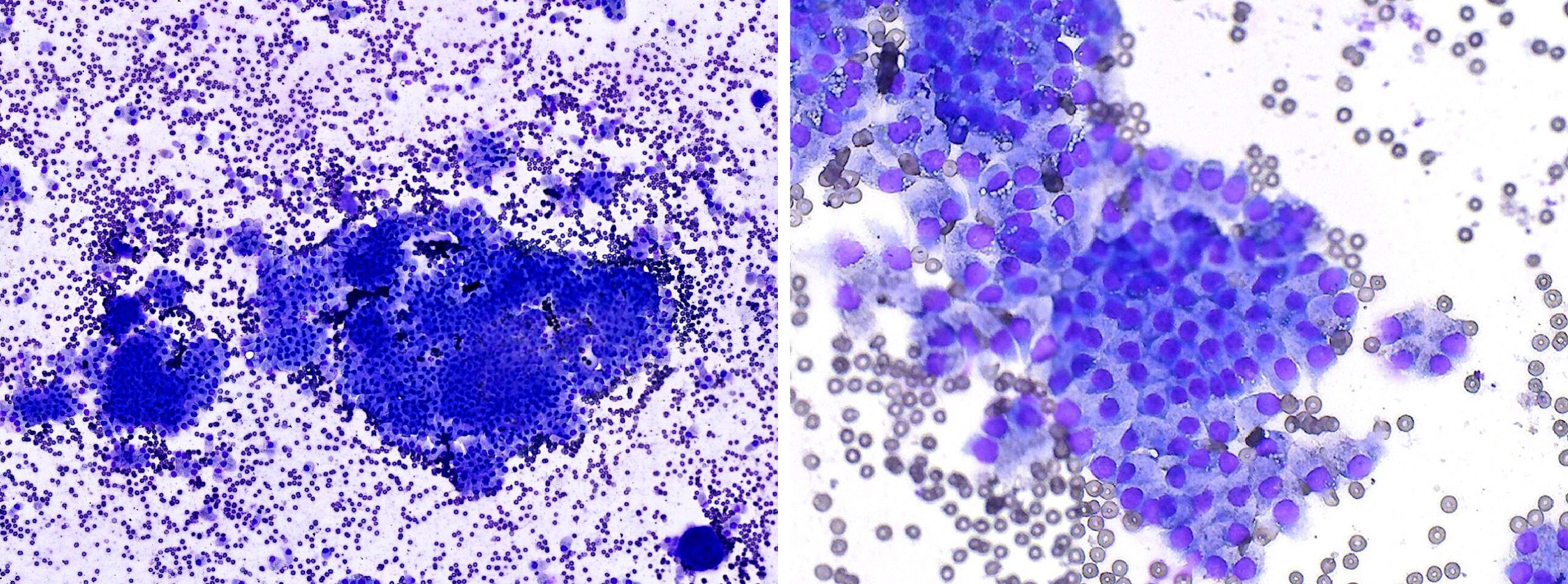

On clinical examination, digital palpation of the prostate was not painful and revealed subjective moderate enlargement. Ultrasonographic examination confirmed symmetrical enlargement with hyperechoic echotexture and evidence of anechoic cystic structures. The main differentials based on clinical presentation were benign prostatic hyperplasia, prostatitis and less likely prostatic neoplasia. Prostatic wash was performed and submitted to an external laboratory for analysis (Figure 1).

The aspirate contains large numbers of nucleated cells on a clear background with numerous red blood cells. Cells are cuboidal in shape, small and arranged in variably sized clusters with honeycomb arrangement, which is typical of prostatic cells. Cytoplasm is lightly basophilic, moderate in amounts, with variably defined borders.

Nuclei are small, round, with smooth chromatin and poorly visible nucleoli. Anisocytosis (cell size variation) and anisokaryosis (nuclear size variation) are mild and cells do not show other signs of atypia. Rare leukocytes are seen and are likely blood derived.

A diagnosis compatible with benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) was found.

Orchiectomy was performed. Following castration, prostatic involution became evident within a few weeks and was complete within a few months.

BPH is an increase in the size of the prostate’s epithelial cells (hypertrophy) and their number (hyperplasia), with the latter being predominant in dogs.

Intraparenchymal fluid cysts may develop in association with hyperplasia. These cystic structures can make the organ susceptible to infection from bacteria ascending the urethra, as accumulated prostatic fluid is an excellent media for bacterial growth; therefore, concurrent prostatitis may be observed.

BPH accounts for more than 50 per cent of cases of prostatic diseases in dogs and its prevalence is greater than 80 per cent dogs older than six years of age. It is particularly common in entire male dogs, as it develops under the influence of androgen derivatives.

BPH consists of diffuse, symmetrical prostatic enlargement growing outward, away from the urethra. Clinical signs may be absent or include – among others – bloody penile discharge, difficulties in defecation/urination, stiffness and lameness.

Diagnosis is often presumptive based on signalment, physical examination (digital rectal palpation: non-painful, symmetrically enlarged prostate with variable consistency) and ultrasonographic findings (diffusely hyperechoic often with parenchymal cavities).

Further confirmation can be achieved via cytology with transabdominal fine-needle aspirate of the gland or prostatic wash. Cytologically, it is common to observe variably sized clusters of well-differentiated prostatic epithelial cells with no significant signs of atypia. Leukocytes may be increased in numbers in case of concurrent prostatitis; bacteria may be seen in septic processes.

Serum canine prostatic-specific esterase has been recognised as a valid and specific biomarker for non-invasive diagnosis of canine prostatic disorders. Elevated values indicate the presence of prostatic disease, but are unable to differentiate between BPH, prostatitis, and prostate neoplasms, as values may not differ significantly among specific pathologies. Treatment for canine BPH focuses on reducing the size of the prostate, with castration being the most effective procedure. In breeding animals, medical management may also be considered.

A recent retrospective study on canine benign prostatic hyperplasia showed that the majority of cases (18/25) had prostates that were equal to or smaller than expected rather than enlarged, suggesting that subjective prostatic enlargement may be overdiagnosed in intact male dogs. This may be partially attributed to the fact that in several countries, most dogs are neutered at a young age, and many practitioners are not accustomed to examining prostates in intact male dogs; therefore, they may perceive the prostate of an aged intact male dog as enlarged when it may be of appropriate size for that dog’s age and weight.

Registered Veterinary Nurse (Part Time)

£30,000 per year

Warren House Veterinary Group

Glenrothes, Fife

Registered Veterinary Nurse (Part Time)

£30,000 per year

Warren House Veterinary Group

Glenrothes, Fife

Registered Veterinary Nurse (Part Time)

£30,000 per year

Warren House Veterinary Group

Glenrothes, Fife